Amid the stress whirl of bumper-car traffic and the holiday “frantics” sits an inward-looking art show, a place of certain calm in its consideration of ourselves, others and the organic machinery that makes us tick.

Years in the making pairing U of A’s Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute (NMHI) and the university’s Faculty of Arts is the brain/mind exhibition, Connections: Bringing Neuroscience and Art Together.

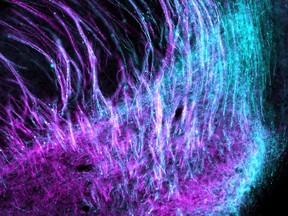

“Connections is a collection of artwork and scientific images that portray aspects of neuroscience, brain disease and mental health, and their intersections with art and life,” to quote co-curators Simonetta Sipione and Marilène Oliver in the project’s book-length catalogue.

Brains loom large in the show’s imagery, from a microscopic photograph of tree-like cerebellar white matter to a striking symbolic collage portrait of dementia by U of A drama student Heunjung Lee of her husband’s grandfather.

Participants include neuroscientists, patients, caregivers, clinicians and accomplished local artists like Richard Boulet, Liz Ingram and Bernd Hildebrandt, Gloria Mok, aAron Munson and Brad Necyk — many of whom have experience with mental health issues.

The central idea of “connection” is an important catch-all, given this wide range of participants and their work, shown in this well-designed setting at the Royal Alberta Museum, which runs through June 22.

Oliver explains how she and co-curator Sipione arrived at the title.

“It came from Simonetta showing us her microscopy images and saying that neurological disorders come when the brain are blocked or if they break, and we were like, ‘Should it be called Disconnection?’

The project team — including designer Gillian Harvey and writer Daniel Laforest — dropped the “dis” and chose something more positive.

This in-person show at RAM is thus the culmination of years of work.

Walking through it, there’s something cleverly comforting about it all: augmented microscopic brain scans flowing room to room into tender artistic depictions working vulnerably through personal trauma.

There’s a repeating sense of a colourful healing garden, albeit via neural pathways and mushroomy brain cells, or the triptych of symbolic stained glass pieces by chronic pain sufferer Hélène Charette — who has close ties to someone with a brain injury — clinical systems researcher Michelle Charette and York university anthropologist Denielle Elliott.

What it all boils down to is we’re all humans enduring the tests of nature and nurture, so — in at least this sense — we do it collectively and together.

The show is split into three parts: The Beautiful Brain, Broken Threads and Healing.

In the first section, as an example, we find Sarah Treit’s floral digital image of the corpus callosum, a sort of feathery ridge connecting our brains’ right and left hemispheres. Meanwhile, medicine degree holder and research assistant Diego Ordonez’s coyly-named Pollock in a Petri Dish is an alluring nest of microscopic connections between neurons and star-shaped astrocyte cells.

Richard Boulet’s striking textiles directly bump up against mental health here, while Fateema Muzaffar’s self-portrait as a tree being pecked at by incessant red-headed woodpeckers of negative thoughts is vulnerable and striking.

Over to the third section, Healing, we find a hanging centrepiece of Ingram and Hildebrandt’s collaborative work — their work ever shrine-like — Light Touch, with Ingram’s MRI brain scans printed on silk, combined with Hildebrandt’s carefully deployed poetry.

Also in this hopeful section, Paul Brain’s paintings of, indeed, his brain, inspired by the artist suffering intracerebral hemorrhage caused by arteriovenous malformation and depression, which made speaking difficult for him and reading and writing nearly inaccessible.

One of the show’s most moving pieces is by co-curator Oliver herself.

The British printmaker, sculptor and multimedia explorer is an associate professor of Fine Arts and coordinator of Media Arts at U of A, an accomplished artist whose MRI-scanned body you could virtually walk through in the landmark, technology-confronting show Dyscorpia in Enterprise Square in 2019.

Her outstanding sculpture in this show is a pair of anonymous hands holding a 3D-printed scan of her mother’s brain under glass.

“My mother was diagnosed with early onset Lewy Body Dementia when she’d just turned 60. All dementia is awful, and I cared for her quite a bit,” says the artist.

“I remember at that time, you’re very isolated, you’re very alone, and you’ve got a lot to do, emotionally.

“And you know just so many people are going through it.

“And then my mother, in a moment of clarity, said, ‘You have to make art about this.’

“I made a number of artworks afterwards, thinking about the experience of kind of being forgotten by my mother, and the way that she was treated in society, the shame around dementia.

“You have no power to help them, and she had to be cared for in a nursing home at the end of her life and that was just so hard as well, to not be able to care for her,” says Oliver.

This level of emotion and heartbeats throughout the show, and some of the hope in bringing all this work together is already bearing fruit.

“At the opening, seeing the joy on the artists’ faces — a number of them meeting each other for the first time — was incredibly joyful,” says Oliver.

“There’s no doubt we’ve created a new community with this exhibition, this whole project. And we’re really hoping it will grow. We have other events happening and there’s no reason why this collection can’t keep growing.”

“People can reach out to NMHI and make art and share it, and we want to help facilitate that,” Oliver says. “That’s what I fight for the most in my career, to keep art and science working together and keeping the audience involved and choosing that conversation.”

Connections: Bringing Neuroscience and Art Together

Where: Royal Alberta Museum — 9810 103A Ave.

When: Through June 22

Tickets: Free with RAM admission ($21/general, $14/seniors, $10/youth, $50/family)