“Death is a part of life, death is a part of life, death is a part of life.”

That was the mantra that pounded in my brain as I drove to New York City, boarded a flight to Zurich with my sister Nancy to be at the bedside of our beloved sister Kate when she ended her life by voluntary assisted death.

It was not a surprise to be going to Pegasos, a voluntary assisted dying nonprofit in Basel, Switzerland, for Kate’s death. She and I had discussed this day and her desire to be in control of her own death process since her diagnosis of stage 4 neuroendocrine cancer in April 2022. Our conversations were heartbreaking and beautiful, poignant, real, scary and often just funny.

When she was first diagnosed, she declared in a matter-of-fact, isn’t-life-strange tone of voice, “Amy, I think I am needed elsewhere.” She was telling me as clearly as possible that she knew in her bones where this was heading. Her words were plump with the mysterious wisdom reserved for shaman, medicine people, energy workers and healers.

I shared Kate’s belief that our human bodies are simply vehicles, temporary containers needed in this world so that our souls can learn and grow. But still, I loved my sister Kate in this body with the long, graceful fingers, the eyes filled to the brim with wisdom, the thick head of blond hair — the perfect topping that barely tethered her to the Earth.

My sister Nancy and I purchased business class tickets knowing full well the impossibility of being emotionally present at this sacred ritual with no sleep. However, sleep did not come easily — five glasses of champagne, 20 mg of THC and 1 mg of Ativan later, I was still wide awake. I could not knock myself out of the awareness of what the next 36 hours would bring. As Nancy and I were rushing from the United States to be at Kate’s side when she died, she was saying goodbye to her beloved home in Menton, France, and driving with her husband to join their adult sons, Peter (with his partner, Marion) and Max, in Lausanne. We all arrived in Basel around the same time. Nerves were frayed, tears were overflowing, but so was laughter. This was a time to rejoice and grieve — to celebrate this sister, mother and wife who had just turned 64.

Before we gathered in Kate’s hotel room to meet with the doctor, we joined Kate in getting her hair washed and combed out at a local salon — no leaving this Earth with a flat top! My sister was always the most effortlessly stylish person in any group. We also stopped at a cosmetics store for the right eye shadow that would cover the dark circles that went hand in hand with her striking, deep-set, blue eyes — a gift from our mother. While getting her hair done, she sent her husband out for adult diapers, not wanting to soil her final outfit (comfortable white linen) when she finally passed. No stone was left unturned. She gave us each homeopathic remedies for grief. In this she failed — not understanding that the pain we would each feel at her death could not be mitigated by ignatia amara.

Kate began letting go the minute she was diagnosed with cancer. She knew that most of the treatments recommended for her cancer would be impossible, perhaps even lethal, given her severe mast cell activation syndrome. At the time of her diagnosis, we were two years into the COVID pandemic and the world was a mess. The state of the world was a frequent topic of conversation in our daily conversations. The chronic violence, severe climate change, people turning away from nature and books and being devoured by technology. It often felt like she had an inside view into the demise of the world and part of her was quite happy to be getting out before things got even worse. If not for her beloved boys, she no doubt would have left much earlier. She was not ambivalent.

The day she died we had breakfast together at the hotel dining room — it is hard to know what to eat when someone so dear is about to die. While eating her final meal, she began shedding her belongings for the final exit. She handed Peter a small tin container with Peter Rabbit on it and then took off a stunning Japanese earring to put in it. The other earring went directly from her ear to Max’s hand. She handed me the watch she was wearing, a delicate rectangular piece of jewelry with small diamonds surrounding the watch face, which now has replaced my bulky smartwatch. She handed me her down jacket and elegant navy blue pants to pass on to my daughter.

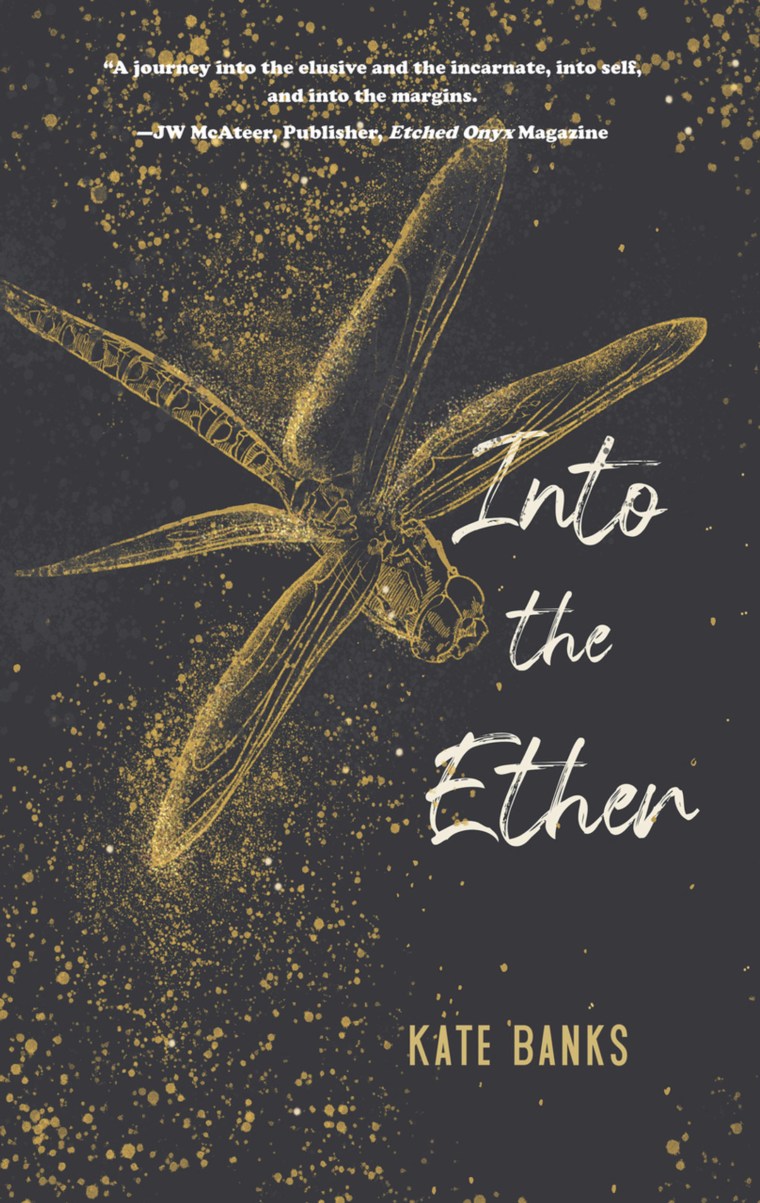

We arrived at Pegasos mid-morning. It was a tastefully decorated warehouse building with two rooms. Mostly I remember the white walls and ceiling, and the plants, as if we had walked directly into heaven. In the first room, the business of death was managed. For at least an hour, Kate and her husband, Pier, filled out the paperwork while Peter, Max, Nancy, Marion and I lounged on a couple of couches, unable to contain our anxiety, worry and grief. The prelude to Kate’s death unfolded in slow motion. She had asked me to pick out a couple of poems from her yet-to-be-published collection of poetry to read aloud. I tried to pick poetry that captured not only Kate’s essence but also her belief system — the one that argued that death with dignity was not only her human right but the only effective way of freeing her soul from this now sinking ship.

Kate knew what she had and how severe it was. During the almost two years she lived with neuroendocrine cancer she did everything possible. She and her husband researched and tracked down every study, every fact about the disease and its treatment. She sought out traditional and alternative healers all over Europe. Cryotherapy, rife machines, supplements, herbal remedies, a personalized vaccine regimen and even peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, a treatment she was quite sure pushed her immune system over the edge, causing symptoms that were simply unlivable. As her body shrank, the tumors in her liver kept growing, pushing her diaphragm up against her lungs, making it hard to breathe. By the end she was not sure where the myriad of symptoms were coming from — the cancer or the treatments, carcinoid crisis or mast cell activation. In her mind none of it mattered. What she cared about was that her life had shrunken down to a dot — days filled with breathing and not a lot else, nights often spent in terrible pain, vomiting, fainting on the floor. In the last week of her life, she told me she was already partly gone — maybe a third. And I felt it. She was hanging on for her boys, but even that became too much. She could no longer garner the energy to meet them in this life. It was time.

We joined her in a second room with a large bed. Kate, sitting up with an IV in her foot, was the image of an angel, dressed in white linen against a light blue sheet, with a large smile on her face. We gathered at the bedside — each of us moving in and out until eventually she cradled both boys’ heads in her arms as they laid down beside her. Their faces were contorted in the deepest grief imaginable. While the peaceful, slightly haunting music she had picked out played in the background, I read her poems — the last of them, “Into the Ether,” perfectly capturing her belief in what we were all doing and where she was headed.

Will it hurt you ask,

When Body bellows its last few breaths and Soul stirs,

Preparing to take leave of the dense moorings of skin and bone,

Struggling to detach from the shreds of Body

That still cling to Life,

The taut tether of earthly existence.

Once again that spiteful sting of separation.

Have you forgotten that you’ve done this again and again?

Perhaps death is not what you think.

Take heart.

The lingering soul is not yesterday’s lover, slipping off at dawn,

Or the setting sun, turning its back on day.

There is no haste, no harsh good-byes,

Nothing, but a tender longing as Soul hovers over Body,

Contemplating its wounds with tender regard,

Casting a quiet dignity on the ache of ages.

The journey towards wisdom is long and hard.

It’s a time of reckoning

As soul tends to the chores of packing up,

Mapping memories, cataloging regrets,

Words unsaid, deeds undone.

Speak heart

Of your comings and goings,

A treasured child,

Body’s rewards for the searing pain of birth

At the service of soul,

The death of a beloved.

There is a merging and melting of boundaries

As Soul bows before its temple to bid it goodbye.

“Thank you, Body”

And maybe, for the first time,

Body feels embraced by love.

The Body is cast off gently,

An item of well worn clothing, soiled and scarred,

And Soul leaves home, closing the door.

At last Body is free to begin its own exodus,

And Soul left to lift its wings and fly into the ether,

Homeward bound.

It’s good to be home where Soul

Meets Self

And finally is told, “you did well.”

After saying individual goodbyes to each of us, Kate opened the cannula, self-administering a dose of pentobarbital directly into her vein. She was literally surrounded in a cocoon of love. Her two boys, on either side of her, repeatedly telling her they loved her. Her husband by her side, hands clasped in prayer. Marion to the left of her, hand on a leg. Nancy at her feet and me on the right side of her body. The end was rather anticlimactic. Within a minute, her head and neck extended and she was gone. I sat holding her hand for another few minutes knowing full well her soul had already moved on.

An hour later, after the police and coroner came to verify the death, we were free to go, to start a life without this incredible person who was at the center of all our lives. We went to lunch, popping our grief remedies, and were left to digest the courage we had witnessed alongside the unspeakable grief we were all feeling. I struggled to imagine how to take the next step in life with only my memories and Kate’s words to guide me on this Kateless path.

Her last poem in “Into the Ether,” her memoir-in-verse that will be posthumously released in October, “What Do I Leave Them,” captures the dilemma of sharing this surreal experience:

How can I catch a corner of a cloud,

Or a patch of blue sky,

The song of a sparrow,

The blink of a lizard,

Or one of those stars that nosedive across the night sky curdling

My tummy?

I could press a leaf or a wildflower into

One of my favorite books,

Or pilfer a feather or a tree pod

From the forest floor.

But the trouble is,

They perish,

And things that don’t,

Well, they’re not worth it.

Sure, there are memories,

But they fade too,

And I’m left with the same dilemma.

How do I leave them a snippet

Of the beauty and wonder I see

Each time I look out at a world.