Alarming rise of assaults, stabbings, shootings and machete attacks have made work a living hell for doctors and nurses

After the sixth blow to her head, Natasha Poirier stopped counting.

She felt certain she was going to die. “He is here to hurt me, and hurt me badly,” she remembered thinking before slumping to the floor on her knees.

Her attacker would later claim he’d blacked out, that he couldn’t remember a thing except high-pitched screams, a defence the judge in his criminal trial rejected.

He was angry, New Brunswick Provincial Court judge Yvette Finn would rule, he was aware of what he was doing “and simply did not care.”

One mid-afternoon in March 2019, Poirier, then a nurse manager in the fourth-floor surgical unit at Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont University Hospital Centre in Moncton, N.B., was cornered in her office and beaten by Bruce Randolph “Randy” Van Horlick in a wholly unexpected, unprovoked and vicious assault, “a flagrant and outrageous assertion of power” over an innocent victim, as noted by one judge in a summary of the case.

Van Horlick, 69 at the time and twice Poirier’s weight, was unhappy that his wife had been moved from a quiet room down the hall to a room closer to the nurses’ station when he went looking for Poirier.

After poking his head into Poirier’s office and informing her she had a major problem on her hands and three seconds to decide what she was going to do to fix it, Van Horlick pulled Poirier by her hair from her chair, punched her multiple times on the head and threw her twice against a wall.

He was sentenced to six months incarceration and two years’ probation for attacking Poirier and a second nurse who heard her boss’s screams and lunged at Van Horlick to pull him off. He assaulted her as well, before returning to battering Poirier, court heard.

Six years later, Poirier suffers the lingering symptoms of a brain injury. Her thinking slows as the day wears on. She gropes for words, has trouble expressing her thoughts, is sensitive to lights and sounds, tends to get emotional and struggles with “pretty severe” post-traumatic stress disorder.

It took two men to drag Van Horlick off her.

“Who would have known, in a surgical unit,” Poirier said of the attack.

Violence knows no limits

Violence against nurses and other hospital staff most often occurs in the emergency department, though it doesn’t discriminate and there’s a growing sense of alarm that a decades-old problem is becoming more frequent, more severe and more reprehensible. “People’s health and lives are at stake,” medical and nursing leaders recently warned.

Who or what is to blame? There are many factors. An increasingly hostile and toxic world. A distressed, overcrowded and understaffed medical system that’s led to dangerous waits for care and boiling frustrations. Violent patient behaviours driven by drugs, psychosis and dementia. And inconsistent or inadequate security in hospitals, with no real accountability for the laxity.

In Halifax, a 32-year-old man is facing nine charges, including attempted murder, after three employees at the Halifax Infirmary were attacked with a knife in late January, stabbing two, injuring the third, and forcing the temporary closure of the emergency department to all but those in life- or limb-threatening situations.

On Christmas Eve, a 33-year-old man brandishing a .22-calibre shotgun barricaded himself inside a hospital chapel in Thompson, Man., aimed his rifle at staff and blew a hole through the chapel window before he was apprehended by security.

This is not solely a Canadian phenomenon. Violence and hostility against health-care workers, including surgeons, is surging south of the border.

“Surgeons being assaulted, battered or killed is a fairly new phenomenon within civilian hospitals,” Dr. Jay Doucet, director of the trauma division at the University of California San Diego Health, said in a bulletin from the American College of Surgeons in October. Six surgeons have been killed in recent years, including a renowned elbow, hand and wrist surgeon, shot and killed by a patient inside a Memphis clinic last year.

In February, a man armed with a pistol, zip-ties and duct tape took staff members hostage inside a Pennsylvania intensive care unit before he was killed in a shootout with police that left one officer dead. He believed more could have been done to save his wife from a terminal illness, CNN reported. In January, a new California law that increases jail time for those who assault ER workers, from six months to one year, went into effect.

In Australia, emergency room violence has reached “crisis” levels, doctors there are reporting. One Melbourne heart surgeon was killed with a single punch to the head after asking a man to stop smoking outside his hospital’s entrance.

High-risk time bombs

Hospitals can be unnerving places, and emergency departments with their triage lineups, packed waiting rooms and high-stress illnesses, are like high-risk time bombs. Like the headache that’s really a hemorrhage, they are the 24/7 unconditional place for people in crisis and the default destination for people who can’t get care elsewhere.

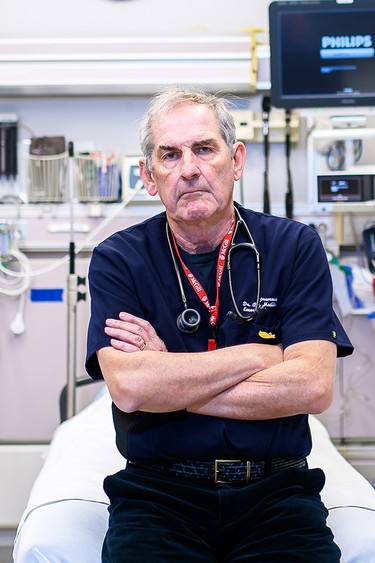

And all too often, tighter security, “extra measures,” is an afterthought, an “after-the-fact-ism” response, said Dr. Alan Drummond, an emergency and family physician in rural Eastern Ontario. Drummond has pushed for safer emergency rooms for patients and staff for much of his 40-plus year career, and recently warned that an active shooter could walk into many hospitals with a gun and unleash “unimaginable savagery.”

“Unless someone gets shot, nothing is really going to happen,” he said in an interview with National Post.

The violence happens in ERs, maternity wards, psychiatric units, geriatric floors. It comes in varying forms and degrees. “I would hate to think that violence is strictly defined as someone who is punching me out,” said Drummond, who co-authored a position statement on violence by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. He includes name-calling, slurs, threatening gestures, clenched fists, “the kind of low-level violence that forces many of us to say, ‘What the hell are we doing here?’ I come here to help people and people are telling me to f–k off and threatening to punch me out. I could do fine in a very controlled office setting.”

Hospitals train staff in de-escalation and the use of chemical (meaning sedating drugs) or physical restraints: how to defend themselves. But many anti-violence interventions and protocols put the emphasis on the individual health-care worker — the victim — to dial down and contain the danger. Drummond said not all hospitals take security obligations seriously and are slow to put in safety measures like security cameras, metal detectors and direct lines to police.

I come here to help people and people are telling me to f–k off and threatening to punch me out

Dr. Alan Drummond

“You can try all the de-escalation techniques you want,” one person who said they spent 15 years working in an inner-city ER posted on Reddit following the machete threat in Port Moody. “When someone is intoxicated and/or psychotic it can be futile.”

Violence has escalated since COVID, surveys and anecdotal reports suggest. Anti-government protests, misinformation and distrust of experts stoked tensions. People today just seem more OK about being openly angry, said Dr. Carolyn Snider, former chief of emergency medicine at Unity Health Toronto-St. Michael’s Hospital. And not just in hospitals. “I’ve seen it across all parts of my life,” Snider said.

“When people lose control over what’s happening, a very common reaction is anger.” It’s a normal human reaction. How people manage their anger is key to being able to manage it in times when we’ve lost control over our surroundings, she said. “That becomes more difficult when you’re feeling scared, when you’re feeling unwell and you’re feeling desperate.”

Add in the lack of basic needs, such as shelter or food — emergency visits by the unhoused are soaring — or even a warm hospital bed instead of a cold, hard ambulance stretcher, and it becomes all the more difficult to manage that anger and loss of control.

The emergency department “is a cesspool for all of that,” Snider said.

But it’s not normal, it’s not OK, and it’s not acceptable for people to be injured at work, she said. It’s not a matter of, “that’s what you get for working in a downtown ER,” or any emergency department, Snider said. “And that needs to continue to be said.”

It’s difficult to get a handle on the true magnitude of the problem because workplace violence in hospitals is under-reported and underappreciated, Drummond said. Horrifying shootings and stabbings are extreme. “What doesn’t hit the media is the daily amount of bullshit that goes on in our emergency department with people yelling at us, throwing stuff at us, biting and punching,” he said.

In an appearance before Parliamentarians studying the issue in May 2019, two months after the assault on Poirier, Drummond ran through the grim statistics: health-care workers face a fourfold higher risk of workplace violence; 50 per cent of all attacks occur in emergency departments; the degree of violence is escalating and has a demoralizing effect on staff. Ontario alone loses $23 million annually in absenteeism and time lost to injuries.

Nurses bear the brunt

Cases tried under workplace laws were equally unimpressive. The researchers found five cases involving violence against nurses where an employer was charged under Ontario’s Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA).

In a “Code White” attack, the second highest level of threat behind an active shooter, at the Royal Ottawa Hospital in 2012, a patient attacked two nurses and a personal support worker, choking one woman to unconsciousness and punching and choking two others. The hospital was acquitted of all three charges under OHSA and two nurses were criticized for going “into hiding” during the wild rampage and not doing enough to help their colleagues.

The “it’s part of the job” mentality might explain why passive acceptance of violence against nurses persists, the authors wrote, and why people tend not to report violent or abusive behaviour. “Because nurses say, ‘What the hell is the point?’” said Drummond. “‘The administration is just going to ask me what I could have done differently.’”

Nurse Poirier said she was asked that very question, five days after Van Horlick struck her so hard across her nose it left her with a deviated septum.

Canada’s Criminal Code was amended in 2021 to create a new intimidation offence for conduct that’s meant to “provoke a state of fear in a health professional” trying to perform his or her duties. But not even that is proving much of a deterrent. Since becoming law, the amendments — which included that courts consider an assault against a health-care worker an aggravating factor in sentencing — haven’t been widely enforced and don’t appear to be making an impact, the authors of the legal analysis said. “On the contrary, during the anti-vaccination protests, health-care workers were encouraged to avoid wearing their work uniforms so they would be less identifiable to possible assailants.”

Departments of despair

But emergency departments across the country are also increasingly places of despair. Eight-, 10-, 12-hour or longer waits. Frail, elderly and seriously ill people lingering and deteriorating on stretchers crammed into hallways, supply rooms or any empty space. Unsafe nurse-to-patient ratios. Too few beds upstairs to admit people while the sick keep coming. Emergency departments have been left holding the bag for family doctor shortages, inadequate long-term and home care, post-op patients who are told to “go to emergency” if they develop a complication outside their surgeon’s office hours, and other system-wide failures, advocates who’ve been pushing for reform have said.

“We can put in metal detectors,” Drummond said, policies nursing organizations throughout the country are pursuing. “But we’re still going to have violent acts by people who are pissed off by the anxiety and concern and the waiting and the insufficient nursing care. Because it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to know that if you’re sitting with your 83-year-old mother, and your mother has been in a hallway for two days in a wet diaper, not getting fed, waiting for a hospital bed, you’re going to get angry. And you’re going to act out on that aggression with the first person you can see, which is usually the nurse.”

When people can’t get the care they need, it’s like popcorn, said Linda Silas, president of the 250,000-member Canadian Federation of Nurses Union. In a packed waiting room, “You have all these kernels … and then you crank up the heat, you crank up the heat. Well, they pop.”

Even if sick, stressed and waiting, “there is no right for you to abuse me, in any way,” Silas said. Violence goes beyond those who are physically harmed, she said. The stress and anxiety touches all who are witnesses.

In the London shooting, gang warfare appears to have been a factor, but it was still terrifying for patients and staff sitting beyond those ER front doors.

Aging and agitated patients

What’s less discussed is an increasingly aging population and an epidemic of dementia, and the behavioural disturbances that come with it. A medical illness can leave people with dementia delirious, confused and highly agitated.

“Everybody gets charging the asshole who was drunk (and) punches out a nurse,” Drummond said. “You can’t legally go after an 85-year-old male who is delirious from his urinary tract infection who throws a urinal at a nurse.”

The acutely intoxicated who’ve been drinking or using drugs or stimulants often must be physically restrained and sedated because they’re not in their right mind, said Ottawa emergency physician Dr. James Worrall. “I can’t count the number of times I’ve had nurses or others say, ‘This patient spit on me.’”

Emergency is, in some sense, the right place for a person in such a state, so they can be safely monitored until they sober up, Worrall said. “It doesn’t mean it’s pleasant caring for that person.” And the solution isn’t to be found in the emergency department, he said. “It has to do with the rise in substance-use disorder in our society and all the factors that go into that.”

The other big category is the patient who is “demanding, threatening, aggressive, often verbally abusive, less physically so, because they’re unhappy,” Worrall said. “And that is a huge, huge problem and the one that, in some senses, we find the most stressful.”

If you’re wondering why ERs are closing, why nurses are leaving the profession, part of it is the (abuse and violent behaviour) wears you down.

Dr. Alan Drummond

Worrall understands the frustration when people are told there are 60 people ahead of them and they’re looking at a 12-hour wait. He recently had to listen to a man with bad back and sciatica pain vent about the failings of the system for 20 minutes. He tried to emotionally de-escalate the situation and come up with some way to help him, “and meanwhile I’ve got dozens of other patients waiting.”

“In each case, essentially, the root problem is not really in the emergency department.”

Doctors aren’t immune

Two years ago, a man carrying a hammer and a knife made it past the front check-in desk at London’s Victoria Hospital and assaulted a doctor, an attack that led to “enhanced security measures,” the London Free Press reported, including personal panic alarms for staffers. Eight in 10 doctors responding to a 2021 survey reported experiencing bullying, harassment, intimidation or aggression, with 40 per cent having those experiences “frequently” or “often,” women even more often than men. Paramedics are also seeing a rise in physical, verbal and sexual assaults.

After reviewing their hospital’s security system call database, Dr. Sahil Gupta and colleagues at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto counted more than 20,000 calls related to incidents in the emergency department over a four-and-a-half year period. On average, 61 calls per 1,000 patient visits, with a disproportionate number recorded overnight. Calls ranged from 713 Code White incidents to calls for loitering, suspicious activity or escorting discharged people from the premises. Gupta said the figures likely scratch the surface.

Drummond knows a doctor who had his leg broken by the disgruntled relative of a patient. Another patient brought in by police in a mental health crisis tried to grab a cop’s gun. “You can imagine how that would have gone down. Somebody who is totally out of control, maybe psychotic, and reaching for a policeman’s pistol in a totally unprotected emergency department.

“If you’re wondering why ERs are closing, why nurses are leaving the profession, part of it is the (abuse and violent behaviour) wears you down,” said Drummond.

Security and accountability

Among the signs of whiplash, swelling of her face and numerous other injuries Poirier’s family doctor recorded in the months following her assault was an area on her head “with various hair lengths.” When police arrived to arrest Van Horlick, they found clumps of Poirier’s hair on her office floor.

She remembers hearing a knock on her door that March afternoon. Remembers looking up and seeing a man she didn’t recognize.

Van Horlick had never seen Poirier before, never talked to her, never saw her on the surgical floor. “Didn’t know who she was from Adam,” he testified at his criminal trial.

He’d had little sleep the night before. His wife, who had diabetes and was prone to seizures and infections, had been admitted days earlier for a wound that wouldn’t heal. At her doctor’s orders, she’d been moved to a bed closer to the nurses’ station for closer monitoring. The person in the room next to his wife was hollering a lot, there was a “a lot of action going on” and he was worried about his wife “big time” when he went looking for the head nurse.

Poirier had never seen Van Horlick before he stuck his head inside her door. “We got a really major problem, and it needs to be fixed right away,” Van Horlick told Poirier after she invited him to take a seat across her desk. She was overseeing 26 patients and 53 staff, so she asked his wife’s name so she could check the patient records. After two minutes or so, he leaned forward in his chair, uttered the “three seconds to decide” threat and then he was up, pulling Poirier from her chair, twisting her arm backwards as well as three fingers, court heard. When other nurses heard her screaming “venez m’aider “ — “come help me “ — they thought it was a patient.

At one point, dazed, bleeding and lying on the floor, Poirier could see shoes outside her door. “I see the feet come back and I pray and I pray and I pray that those feet, those brown shoes, come back, and he did,” she testified. The shoes belonged to Guy Cormier, a clinical nurse specialist who, upon entering Poirier’s office, saw Teresa Thibeault, the nurse practitioner who’d rushed to help Poirier, trying to protect Poirier, who was trying to cover her head.

The “incident” lasted, in all, about 11 minutes, according to court documents.

Van Horlick had been his wife’s caregiver for much of their 21-year marriage, the court heard. She died in December 2019. He’d held a variety of jobs over the years — transport driver, fisheries officer, cattle-ranching. He didn’t deny that he assaulted Poirier but had “issues” with the severity of her injuries, court heard.

He ultimately failed in his defence of “non insane automatism,” his claim that he was in a dissociative state at the time. That “everything went black,” until the next sensation he experienced was “her (Poirier) screaming and it hurting my ears,” followed by two men trying to pull him down, according to trial transcripts.

“I think (one) said, ‘You’re not supposed to hurt a nurse,’” he testified.

Van Horlick testified that he hadn’t set out to resort to violence and that he knew it was wrong to hit Poirier, but that he was angry about the position he claimed he’d been put in.

“When looking at the whole of the evidence,” New Brunswick provincial court judge Yvette Finn said while reading from her notes in finding Van Horlick guilty of two counts of assault, “I conclude that Mr. Van Horlick developed throughout the years the perception that he had more knowledge than the medical profession in the treatment of his wife and that he was entitled to give orders that had to be followed or there would be consequences to those who did not follow his orders.

“On March 11, 2019, it is exactly what happened.”

The National Post attempted to reach Van Horlick through lawyers who represented him at his trial and sentencing hearing. However, they did not respond to email requests.

Poirier, who required surgery for a deviated septum and three surgeries to her left hand, was unable to return to her job as a nurse manager, or any equivalent occupation. She sued Van Horlick and, in 2022, was awarded more than $1.3 million in damages for lost past and future income, pain and suffering. Van Horlick failed to file a defence. During an examination after judgment hearing, Van Horlick told the clerk he had no money and walked out of the court, warning he could “snap again.”

Unable to return to her old job, Poirier was eventually fired by her employer, who was later ordered to pay Poirier $40,000 for failing to accommodate a return to work.

A nurse for 26 years, she loved nursing. In addition to her job at Georges-Dumont, she worked part-time for Veterans Affairs, helping vets with PTSD. She loved working with different patients in different areas: Nursing homes, prisons, hospitals.

Poirier now has a service dog, a Shih Tzu named Harvey, trained to respond to signs of anxiety or cues of a pending panic attack. He blocks from the front or back when they walk in public and crowded places. He distracts her when he senses her PTSD rising, pawing or barking at her until she calms down.

It wasn’t her first experience being assaulted. Early in her career, she was kicked in the stomach by a patient in a psychiatric unit. “I was seven, eight months pregnant at the time.”

“We’re made to think we’re not good caregivers because we get assaulted,” said Poirier, who has a new book out, Unsure: Bearing Witness to Justice. “We’re blamed. There’s a fear of judgment, retaliation, losing our jobs and being seen as weak.

“People are not filling out incident reports because they don’t think it’s going to change anything, and they just suffer in silence. It’s really a culture that needs to be broken.”

Six months after Poirier’s attack, a nurse in Abbotsford, B.C., was struck in the face by a patient with a dumbbell, breaking her upper jaw and cheekbone. It’s not clear where he got the weight. The nurse’s jaw had to be wired shut. She required half a dozen dental reconstructions and gum grafting. The man, who’d suffered a fall a year earlier that his wife said preceded an abrupt change in his behaviour, pleaded guilty to assault and was sentenced to 14 months less time served. A judge found that the man’s “decreased level of consciousness” at the time of the assault reduced his “moral blameworthiness to some degree.” The case was made public by the B.C. Nurses Union and, while it happened on a medical unit, it came just days after the union sent a letter to local health officials over “chaotic scenes” in the hospital’s emergency department, and a lack of safety measures.

Silas sees a gender issue. Nursing and health care, in general, are female-dominated professions. “It’s not only the violence,” she said. “If I look at the fights we’ve had to have for proper PPE, personal protective equipment, for workloads and staffing, it is always an uphill battle when discussing improving the work life of nurses.”

There have been some changes since her union launched a campaign against violence, back in 1991, including Bill C-3’s passage in 2021 of a new intimidation offence against health-care workers punishable by up to 10 years in prison.

But public awareness hasn’t trickled down, Silas said. “In Halifax, they came in with knives.”

The Halifax Infirmary has since installed a walk-through metal detector. Guards are also using hand-held wands.

Windsor Regional Hospital has been using an AI weapons detection system in the emergency department at its two campuses since late 2023. Approximately 4,700 items — knives and “other threats” such as tools, makeshift weapons, drug paraphernalia (needles) — have been detected from 610,000 people going through the detectors. No guns have been identified. Approximately 2,700 of the captured items were knives.

The number of detected “knives and other threats” has fallen from an average of about 17 per day in November 2023, to an average of six per day. “Clearly, ‘word of mouth’ has occurred … and people know now not to bring in these items into the emergency department,” hospital spokesman Steve Erwin said in an email.

Hospitals in Manitoba have committed to putting in an AI system. At St. Mike’s in Toronto, an online dashboard flags and tracks patients who have the potential to be violent or abusive. The tool considers confusion, paranoia, verbal or physical threats and other behaviours to churn out an overall risk rating that can be updated every 15 minutes to provide situational awareness throughout the person’s emergency stay. Another “agitation road map” offers steps to help manage patients at risk of becoming aggressive, even if it means something as simple as providing a warm blanket or food.

In 1999, the downtown Toronto hospital was the scene of a New Year’s Eve shooting that horrified the city. Henry Masuka was shot and killed by police after he took an emergency doctor hostage, holding what appeared to be a real gun to his head, when he was told it would be 45 minutes before a pediatrician could see his three-month-old son.

The gun turned out to be an unloaded pellet gun. An inquest later heard that the baby had only a minor cold.

Snider wasn’t working at St. Mike’s then. There are only a few staff still around from that time. “But that incident, and incidents since then, are embedded, frankly, in our DNA,” Snider said. “That experience changes who you are.”

It also led to new security measures, including passcards to restrict certain areas of the emergency department. Before that, all doors could be opened by anyone.

Controlled access to the ER is among the minimum safety standards groups such as the Canadian Association for Emergency Physicians have lobbied for. Some health authorities contract out security to private companies, where there is no expectation the security officers will physically intervene.

“When I’m touring outside the Lower Mainland, they might have no provision of security,” said B.C. Nurses Unions president Adriane Grande. The union has fought long and hard for improved security. Rural and remote communities often rely on the RCMP. “Is it the RCMP’s job to be the hospital security?” she asked.

“It’s really the lack of employer response that makes nurses feel incredibly betrayed and undervalued,” Grande said. “There aren’t proper investigations, and if there are corrective actions, it’s not clear what’s been implemented and what hasn’t.”

Canada can no longer pretend the violence is an isolated act confined to the occasional stabbing or shooting, Drummond said. Low-level violence happens every day and is forcing people to walk away from the medical profession. “Shine a light on it, call it what it is: a pervasive problem that needs to be addressed,” he said. He may not work in an inner-city ER but people have walked into his rural hospital in Perth with hunting knives.

“We have the expertise in this country to not be stupid about it, but to say, you know, every emergency department should have limited access, everybody should be forced to hand over their hunting knife when they come into an emergency department.

“We have the expertise. We just need to have the political will.”

What’s lost is the effect on patients, he said. “Can you imagine being in an emergency department with your child with a sore throat, sore ear, diarrhea, and across the hallway you’re watching someone throw urine around and telling nurses to f–k off. Or seeing a nurse being physically assaulted. What is the effect on other patients?

“Nobody ever talks about that. But we should.”

National Post