He has never held elected office but the former back-up goalie and global banker from Fort Smith, N.W.T., is ready for his biggest challenge yet

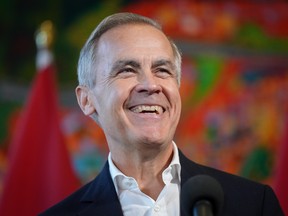

When his victory was announced in a noisy convention hall in downtown Ottawa, Sunday night, Mark Carney slowly rose to his feet, turned to kiss his wife, and started hugging and shaking hands with Liberal party members all around him as music and cheers downed all else out. Once the room quieted, he sat beaming up at one of his daughters, now on stage, as she gave the audience, and the country, a formal introduction to Canada’s next prime minister.

Carney’s sweeping victory, 86 per cent, pushed departing prime minister Justin Trudeau aside as leader of the governing party, and as the new leader stood at the podium scanning the bobbing crowd and swaying signs, he let out a “Wow.”

It might have been an expression of awe, or appreciation, but surely not a wow of surprise. This was a moment everyone expected, at least lately, and some for more than a decade.

It was a moment that seemed inevitable, but also strangely improbable.

While it’s easy to say he was the heir apparent to lead the Liberals, which he was, people who know Carney say it is equally easy to wonder why he would even want the gig, as his opportunity for aggrandizement has always been far greater, and his risk of public blunder much lower, outside of politics.

The inevitability versus improbability dichotomy is really only there because Carney has had an extraordinary existence, a life of shifts and shuffles in Canada and on the world stage, always climbing upward.

Since Carney made his reputation as an economist who likes to talk of productivity and efficiency, it’s appropriate he might celebrate becoming Canada’s 24th Prime Minister on his 60th birthday. Two parties in one, although it’s been a long time since austerity in his personal life has been required.

As an adult Carney has been a globe-trotting private banker just a heartbeat from being named partner in a leading American investment bank, a dream job he gave up to work in the public service, with both those jobs only precursors to his leadership of central banks in two countries, which are the roles that made him famous, at least within financial and political circles.

And now he’s again dropped a well-appointed private life for an uncertain future in the public eye.

“He’s one of those people you don’t meet very often, that once you spend time around him, you realize he’s going places. He doesn’t have to tell you he’s going places you just know it,” said Tim Adams, a former U.S. Treasury Department undersecretary who first met Carney decades ago at meetings of international finance officials.

“You spend time around him and you think, OK, you’re going to run something someday. You’re going to be prime minister. You’re going to do something big,” Adams told National Post in an interview.

Carney’s problem, potentially, is that his life reads like it was purposefully built to present a ready-made political leader, and perhaps it was, but it is one finally complete at a time this particular image is waning. With populism and skepticism increasingly creating distrust of elites, globalism, higher education and the establishment, could it be that Carney missed his sweet spot?

He wasn’t born into that stratosphere — he has that going for him with the anti-establishment crowd. He had a modest beginning.

This is the story of Canada’s next prime minister.

He doesn’t have to tell you he’s going places you just know it

Tim Adams, former U.S. Treasury Department undersecretary

Mark Joseph Carney was born March 16, 1965, in Fort Smith, N.W.T., a village skirting the border with Alberta. Fort Smith sits halfway between Edmonton and the Arctic Circle, and his arrival as the son of a teacher mother, Verlie, and principal father, Bob, helped keep its population above 2,000.

His family moved to Yellowknife when Carney was four years old, and when his father became a professor at the University of Alberta two years later they moved to Edmonton, where Carney grew up with a sister, Brenda, an older brother, Sean, and a younger brother, Brian. He shoveled driveways and delivered the Edmonton Journal newspaper for money. He was an excellent student at St. Francis Xavier Catholic High School, former teachers told Postmedia. He loved hockey, the Edmonton Oilers, and school.

“I think that origin story is very important, and very important to him,” said Adams. “It shows the arc of a career that has so much momentum, to come from where he came from and to continue being really successful.”

Carney left Edmonton in 1983 to build a resume — rather, a curriculum vitae — that sets him apart.

He earned a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University on a scholarship, and a master’s and doctoral degree (all in economics) from the University of Oxford. They are considered two of the world’s best schools, one in the United States and the other in England.

While at Harvard he was backup goalie for the school’s hockey team. While at Oxford he met his British-born wife, Diana Fox, an economist specializing in the developing world. They remain married and have four now-adult daughters.

“To get into Harvard when he got into Harvard, with really no connections, no legacy there, was an extraordinarily hard thing to do, although that was long before I knew him,” said a veteran Bay Street banker who did not want his name published because his firm might disapprove.

Between degrees, Carney worked at Goldman Sachs, an influential American investment bank. He was posted to the bank’s London and Tokyo offices, and after his PhD, he returned to the bank, working in London and New York before returning to Canada as managing director of investment banking in Toronto. Not much says global financial elite more than Goldman Sachs. Not much more says success in that field, either.

“He’s frequently the smartest person in the room but doesn’t seek to make that obvious to everybody else in a way that some do,” said the Bay Street banker.

Carney then made an abrupt change.

“I nearly fell out of my chair when he left Goldman Sachs when he did, because he was on a trajectory to achieve great things and, in that era, at that firm, you joined with one intent, which is to become a partner and retire and be fabulously successful,” the banker said

“He was on the edge of being a partner at Goldman Sachs, which is a very lucrative role, and he chose to leave that role to be a deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, which is not a glory job, and it’s not a particularly well-paid job.”

It was 2003 when Carney joined the Bank of Canada, the institution that oversees the country’s monetary policy. He was recruited by bank governor David Dodge, who reportedly declared he had just hired his future replacement, but Carney stayed just 15 months.

He again made a sudden move, becoming senior associate deputy minister of finance under Paul Martin, a Liberal prime minister. Carney remained there under Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper.

While in the finance department, Carney was credited with handling the final sell-off of Petro-Canada, a government-owned oil company started by then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau, Justin Trudeau’s father. In 2006, Carney managed the controversial implementation of a tax on income trusts.

Alongside Harper’s finance minister, Jim Flaherty, Carney travelled to international G7 and G20 meetings, and the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

He’s frequently the smartest person in the room but doesn’t seek to make that obvious to everybody else in a way that some do

It was at an international meeting where Adams, then with the U.S. Treasury, first met Carney. They were counterparts — Carney for Canada, Adams for the United States. Everyone was huddled around large tables stuffed with ministers and deputies discussing international finance.

“The issues we were wrestling with at the time — it was after 9/11, there was a global war on terror, the economy was starting to weaken, we were going into great financial crisis, there were so many things that were going on,” Adams said.

“I saw then he was a very talented individual and I think everyone around the table did. Mark was just a real thought leader. He was wicked smart, very thoughtful. He’s funny, he’s likeable, he’s strategic.”

He saw ambition in Carney, but not a lot of ego.

“I live my life around ambitious people,” said Adams, who is now president of the Institute of International Finance, a global financial association for more than 60 countries. “I have a board of 50 CEOs. I know what ambition looks like. But he never wore it on his sleeve, he didn’t have to. You just knew that he was going places.”

Where he went was back to the Bank of Canada, this time at the top, as governor, in 2008, an appointment endorsed by Flaherty.

Carney was seen as the outside option, despite his previous short stint at the bank. The business press was enthusiastic for his candidacy, pulling out laudatory, perhaps lazy, descriptors: “wunderkind,” “rising star,” “boy genius,” and “rockstar.” He was called a “golden-haired whiz kid” on CTV. The poor Bank of Canada veteran vying against Carney, who had worked at the bank since Carney was 10, didn’t stand a chance.

While much is made of Carney turning his back on the luxe world of investment banking for public service, it was not a riches-to-rags story. He likely took a pay cut, but the governors’ salary was still about $400,000. He bought a fine house in Ottawa’s tony Rockcliffe Park, but it’s far from the grandest home in the neighbourhood, and it’s where he still lives.

For most Canadians, the Bank of Canada appointment was likely their introduction to Mark Carney. Even economists and savvy investors had few prior public statements from him to gauge what he had in mind.

“I pledge to do my utmost to live up to the very high standards of those who have come before me,” he said when accepting the role.

He took over when Canada’s economy was strong, with the lowest unemployment rate for a generation, even as the U.S. economy slumped, but there were worrying signs on the horizon.

Carney was finally at the top of the food chain in a job, not a deputy or an associate. He was governor. He doesn’t like playing second fiddle.

In his first public speech as governor, on Feb. 18, 2008, he presented his perspective, talking up globalization and international integration. “I chose to speak about globalization at the outset of my tenure because it will continue to be one of the forces shaping our economy and economic policy for years to come,” he said then. His speech was suitably academic, tracing globalization back to the Roman Empire.

“It is incontestable that the current wave of globalization has been, on balance, of great benefit. Hundreds of millions of people have already been lifted out of poverty, with the real potential for hundreds of millions more to share their destiny,” Carney said in that 2008 speech.

For those with an eye on finance, Carney started to become a household name in Canada. With each lurch of the economy, Carney’s pronouncements made headlines: Rate cuts, inflation, stagflation, gas prices, value of the loonie, employment, unemployment, loosening, tightening, and eventually recession, recovery, rebound.

Within nine months of taking office, increasingly dire economic fortunes blew in from the south, and Carney’s name was pushed from the business pages to the front pages. Along with Flaherty, the pair’s words moved domestic stock markets. Within his first year, Carney announced an interest rate cut to an all-time low.

Carney stuck out his neck by steadfastly predicting the economy will bounce back soon. His outlook proved to be rosier than reality, but eventually, it was official: The numbers showed Canada’s recession had ended and a fragile recovery had begun.

Carney and Flaherty both soaked in the acclaim of Canada weathering the crash better than any other major western nation.

That didn’t seem contentious until this month, when Carney became the frontrunner to be the new Liberal leader. Former prime minister Stephen Harper wrote to Conservative party members complaining of “Mark Carney’s attempts to take credit for things he had little or nothing to do with back then.” Harper said Flaherty was the one who made “the hard calls during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.”

In 2010, Carney’s third year as bank governor, Time magazine named him as one of the “world’s most influential” people, pegged at No. 21 among 25 world figures. “Central bankers aren’t often young, good-looking and charming, but Mark Carney is all three — not to mention wicked smart,” the magazine said. U.S. president Barack Obama was No. 4.

Seizing the moment, and his growing reputation, he pushed for greater international banking regulations to guard against another crash.

His stern views on the role of private banks sparked a behind-closed-doors dustup with a powerful U.S. banking boss that quickly became high-level gossip. It put a sharper edge on his reputation, attracting new descriptors: “sharp tongued” and “blunt.” If economists and financiers around the world hadn’t been paying attention, they were now listening to what Carney had to say.

It’s possible that nascent political ambition started to percolate, or perhaps him finding he had a voice spurred him to use it, but from within the rarified world of Bay Street, Carney’s words started to carry a distinctly Main Street smell.

He slapped selfish bankers as being too focused on “opera or the ski slopes of Davos.” He chastised corporate Canada, saying “incomes for the top 10 per cent have increased about twice the rate as incomes for the lowest 10,” and blamed fellow bankers for running “a system that privatizes gains and socializes losses.” He even gave a speech to the autoworkers’ union.

For many Canadians, though, the most obvious thing they likely noticed from Carney was his switch to plastic polymer bank notes.

“Mark has been flirting with politics for a long time,” said a well-connected political observer who is friends with Carney but did not want to be named. Carney had carefully not declared his party support and was courted by Liberals and Conservatives.

“I think he felt he’s kind of purple — a red Tory or a blue Liberal,” said his friend. “Prior to Justin becoming leader, Mark was seriously considering running for leader.”

After an electoral trouncing, Michael Ignatieff resigned as Liberal party leader in 2011. Carney and Trudeau were both urged to run to replace him. Trudeau, seven years Carney’s junior, had public buzz for his famous family, good looks and youthful persona, but was unproven as a leader. When the party opened its leadership vote to allow people who were not paid party members to cast ballots it was a huge boost to Trudeau, who had a massive social media following that could be marshalled.

“Mark knew that he could never compete with that,” the friend said. The rockstar was out-rockstarred.

Around the same time, the Bank of Canada was denying a front-page story in Britain’s Financial Times newspaper saying the Bank of England was courting Carney to be their new governor. When Carney was asked directly about it, he said the article was not accurate.

Soon after, he cut his seven-year governorship short to become governor of the Bank of England.

The prestige and challenge of running the Bank of England — a position considered the most powerful unelected official in the country, and one of the most influential figures in world finance — was immense.

England’s central bank was tarnished by controversy at the time, and its vast private banking industry was dripping with scandal. British media called for a “new, unsullied governor,” with one headline bluntly asking: “Is anyone left untainted?” In those circumstances, being an outsider was a selling feature, although pundits almost choked on the idea of a Canadian being at the wheel.

Having a British wife and degrees from Oxford helped calm the waters, along with the fact that, as a Canadian, he was at least a subject of the Queen, but British bookies gave him six to one odds.

He beat those odds and when Carney was appointed in 2013 by Queen Elizabeth II on the recommendation of Conservative prime minister David Cameron, he was the bank’s first non-British governor in its 318-year history.

In London, George Osborne, Britain’s finance minister, publicly gushed when announcing Carney’s appointment, calling him “the outstanding central banker of his generation.” Carney, in turn, said at the time: “I am going to where the challenge is greatest.”

Mark has been flirting with politics for a long time

Carney immediately became one of the most influential figures in Britain, which meant he became a favourite subject in the news.

After a rush of positive commentary, Carney soon learned the oddity of public life in the land of notoriously nosy media: The tabloids balked at his immense salary, with a housing allowance that pushed his annual remuneration to about $1.5 million at the exchange rate of the day. His first appearance before the U.K.’s treasury committee elicited this description from the Daily Mail: “A jockey’s build and dainty, feminine fingers… the face suggests George Clooney… He peered at the MPs as though he had just taken off his snow goggles.” Welcome to Britain.

He made headlines for replacing a cricket match at the banks’ annual summer party with a game of rounders, and for being caught trying to bring contraband cans of the family cat’s favourite food, Friskies, on a flight from Ottawa, in contravention of import rules. When spotted jogging with a quirky utility belt, or seen at a show with his wife, or relaxing at a cottage in shorts, it made the news, as did his dinner with the Queen at Windsor Castle.

Even after two years on the job, as he turned 50, occasional superlatives crept up, including “the Lionel Messi of global finance.” As a soccer fan — he supports Everton Football Club — Carney must have approved.

Opinions turned much harsher in the leadup to the hotly divisive 2016 referendum on Britain leaving the European Union, the so-called Brexit vote. Carney publicly warned the damage to the economy of leaving could push Britain into recession, sparking howls of protest for entering the political fray. Suddenly, the shine was off, at least for Brexit supporters and euroskeptic media who demanded his resignation. He was called a doom-mongerer, a mouthpiece for establishment fear, and given a new nickname: Mark Carnage.

When he left the governorship in 2020, his Brexit commentary was named his “greatest sin” by the Daily Telegraph, a stain on generally positive reviews. In one of his last messages, Carney encouraged asset managers and pension funds to reduce their exposure to fossil fuel industries in the face of climate change.

He embraced this concern and became United Nations Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, earning an American buck a year in pay, and taking on several corporate roles, presumably for far more money.

He returned to Canada with people pestering if he would run for office, and if so, for which party, and with him still demurring, although his increasingly outspoken views on climate change seemed to give Liberals the nod.

Carney slid into his next phase slowly.

Last fall, to boost sagging morale in the Liberal party at a time when Trudeau insisted he was staying on as party leader, Carney spoke to the Liberal caucus, where he had friends, at a party retreat. He agreed to lead a Liberal task force on economic growth. There was a backroom move to make him Trudeau’s finance minister.

Carney was dipping into direct partisan politics. And he had finally picked a side.

Working with the government may have helped him access the party he would soon be asking to vote for him, but it also wrapped the popularity anchor of Trudeau around his waist. Likely understanding Carney’s maneuvres, Conservative House Leader Andrew Scheer called a press conference to coincide with the Liberal retreat to publicly say that Carney and Trudeau are “basically the same people.”

This January, Carney appeared on The Daily Show for an interview with Jon Stewart, the popular, politically progressive American comedian and commentator.

Carney came armed with gags. When Stewart asked about U.S. President Donald Trump’s threat to make Canada part of the United States, Carney stumbled slightly, then let it unroll: “We find you very attractive, but we’re not moving in with you.” He paused a beat for laughter. “It’s not you, it’s us.” It brought the house down.

Neither Stewart nor Carney were good enough actors during what happened next for it not to scream scripted. Stewart said it’s hard for someone to be a party leader when saddled by an unpopular predecessor, then Carney interrupted: “Let’s say the candidate wasn’t part of the government.”

“You sneaky — you’re running as an outsider,” Stewart said.

Carney smirked: “I am an outsider.”

And thus opened the next chapter of Carney’s life. Three days later he made it official, in Canada, in a speech in Edmonton. Conservatives have since run ads attacking Carney using the sound snippet of Stewart calling him “sneaky.” Welcome back to Canada.

Carney, of course, is an outsider only in the most technical sense of not being a long-time party member, elected MP or in Cabinet. But he has friends in high places, even among those he ran against for leadership. If he was an outsider he was a most thoroughly connected outsider, so connected he was basically inside. The distinction, though, allows him to chastise the Liberals for not showing enough fiscal discipline with a straight face, because he wasn’t at the Cabinet table.

It is one thing to win a party’s leadership. It’s another to win a general election. A series of party leaders have found that out the hard way. An obvious comparison is Ignatieff, who also was praised, like Carney, for his intellectual heft and experience abroad. He failed miserably at connecting with the masses.

It seems unfortunate for Carney that his ascension to the highest office in Canada comes at a time when many of the rules he learned over the decades on economics, governance and the international order have been discarded by the rise of Trump and Trumpism.

That drops two hurdles in Carney’s path, navigating an increasingly sectarian population, and navigating Canada’s deteriorating relationship with the United States amid a tariff war and threats of annexation.

“It’s hard to make the transition from intellectual policy maker to retail politics. But people do it,” said Adams, the former U.S. Treasury official. “I’ve not witnessed him out kissing babies and shaking hands, but he’s a charming guy and he’s personable, there’s some chemistry there.” Adams said Carney is a normal guy; they exchange emails about hockey, most recently on the recent Canada-U.S. hockey games.

Carney maintains an interest in sports. He jogs, he plays tennis, he’s run marathons, he coached his daughters’ soccer teams. He reads a lot. He has frequently said his favourite food is pizza. Is that enough?

“We may face some challenging economic times in coming years, and we may all be happy that we’ve got people in political leadership who know something about economics and who’ve managed through crises,” said Adams.

The Bay Street banker source agrees. Carney wanting to go into electoral politics is as surprising and risky as his previous jump from private banking, he said.

“From the very beginning he’s had a patriotic component to him that has driven him a lot,” the banker said.

“He’s left lucrative senior corporate leadership roles to step in front of a freight train at a 30-point disadvantage, to go be potentially embarrassed,” he said of facing the electorate as Liberal leader. “It’s hard to paint that as self-centred ambition.”

The banker said he thinks Canada needs more international friends in light of U.S. hostilities, and maybe a leader with international contacts isn’t so bad: “You can call them global elites, but we need a better relationship with Europe. We need a better relationship with the U.K., with China, Japan, South Korea.”

Carney seems to understand the zeitgeist. Such are the times that his online leadership campaign biography doesn’t mention Harvard, or Oxford, or Goldman Sachs, or even private banking. It does mention his hockey goaltending as an adolescent.

His introduction to retail politics hasn’t been smooth. He’s already had stumbles, some that seemed easy to avoid. He’s been accused of over-puffing his accomplishments, an accusation spurring a goldmine of amusing online memes that left his opponents delirious.

He wasn’t forthright about the recent move to the United States of the head office of Brookfield Asset Management, a publicly traded company for which he was chairman of the board, and then he didn’t own up to the mistake, or the lie. He was also found not to have yet resigned from some international roles despite saying he had. He spread shockingly wrong information about Canada’s importance in the semiconductor supply chain. In the English leadership debate he spoke in clipped passages, as if reciting PowerPoint slides while struggling to keep it simple.

Behind much of it is politics; street politics at a time when politics has more scrutiny and less elasticity.

His Sunday night victory speech, though, perhaps marked a reset. His delivery was smooth, his message vivid. He wiped out weeks of opposition attack ads that branded him Carbon Tax Carney by announcing he’s dumping the carbon tax. He fiercely challenged Trump’s threats, took swipes at Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre, and defended Canada’s future. And he made several hockey analogies.

While Carney’s friends say voters should focus more on Carney’s big ideas than on small talk and bonhomie, some of his critics say the very same thing.

“He is very good at telling everyone what they won’t have — won’t be allowed to have, more precisely — while falling short of detailing what will be offered in replacement,” Peterson wrote of Carney. He sees Carney’s message as camouflage for tyranny.

That view pushes the perceived stakes to extremes on both sides: salvation versus tyranny.

With such vocal division, a general election — when it comes, probably soon — might well be Carney’s hardest test. Maybe, like when he arrived in Britain, he is again going “where the challenge is greatest.”

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our newsletters here.