I clearly remember the moment on an otherwise average day in December when I slid my hand across the slope of my shoulder, and felt a small bump. It should have been like scratching an itch or brushing the hair out of my face, one of the countless thoughtless actions that we perform each day and never recall.

But I remember that moment, because that bump was the genesis of my developing sepsis, the deadliest condition I had never heard of. Within 24 hours, that little bump on my shoulder would nearly take my life.

My gut instinct when I felt this small bump was to panic. I briefly thought about calling a doctor, but quickly dismissed that notion as absurd. There were just a few hours left at work, and I was eager to hurry home. It was Hanukkah and my kids would be waiting and anxious to celebrate.

Must be a bug bite, I told myself. I pushed the worry away, finished up at work and dashed home to my husband and kids.

The rest of the evening passed in a blur. We lit the menorah, gave the kids their gifts, and I forgot all about the bump. But in the middle of the night, a throbbing feeling in my shoulder startled me awake. I inspected the spot, again slowly sliding my hand across my shoulder. The bump had grown. It felt angry and hot to the touch, but I didn’t panic. I’m just having an allergic reaction to the bug bite, I thought. My shoulder was throbbing and swollen but I willed myself back to sleep.

What is sepsis?

Sepsis, I later learned, is the body’s overwhelming response to an infection. Common symptoms include fever, fast heart rate, rapid breathing, confusion and body pain, according to the World Health Organization. A life-threatening medical emergency like a heart attack or stroke, patients require immediate attention.

Of course, I didn’t know this then as I slept, nor the next morning when I awoke feeling as though I was coming down with the flu.

Or by later that afternoon, when my symptoms worsened and then it felt like I had the worst flu ever.

Or by evening, when my fever was raging and I could hardly move. I was the sickest I’d ever felt in my entire life.

I still thought I had a bug bite and the flu when my husband carried me down the stairs, put me into the car and rushed me to the emergency room that evening.

Too weak to walk, my husband wheeled me inside and after the nurse checked my blood pressure, the ER staff quickly whisked me away with a sudden whirlwind of IVs of antibiotics and fluids.

At some point someone used the word “septic.” I had no idea, lying there in the emergency room, that sepsis is one of the most frequent causes of death worldwide, according to the WHO. I didn’t know that sepsis was my immune system’s out-of-control response to a skin infection that started on my shoulder and now was raging in my body.

While I didn’t understand the big picture, I understood that, at that very moment, my low blood pressure was the problem. It wasn’t responding to the fluids and antibiotics.

Facing death

By now my body was freezing but my temperature was soaring and my swollen shoulder a mass of hot pain. And then, something wonderful happened: I started to feel as though I was flying. It was a marvelous feeling, to be away from the cold-hot misery in my body.

I was gone somewhere in the sky when the critical care doctor came down from the intensive care unit. He was tall, and I thought he was handsome, although I could not focus enough to actually see his face. He calmly explained that I was in septic shock and that my blood pressure was too low. I needed a central line to deliver blood pressure drugs called vasopressors. A delay could mean organ failure and death, he said.

I was still somewhere in the sky when the handsome doctor whose face I couldn’t quite see stuck a needle into my neck. He quickly installed a line to deliver medication, and soon I was off to the ICU.

As nurses adjusted my IVs, the blood pressure monitor’s fluctuations were a barometer telling me where I stood between life and death. I came to understand that either the medications were going to work and my blood pressure would stabilize, or they weren’t going to work.

And then what?

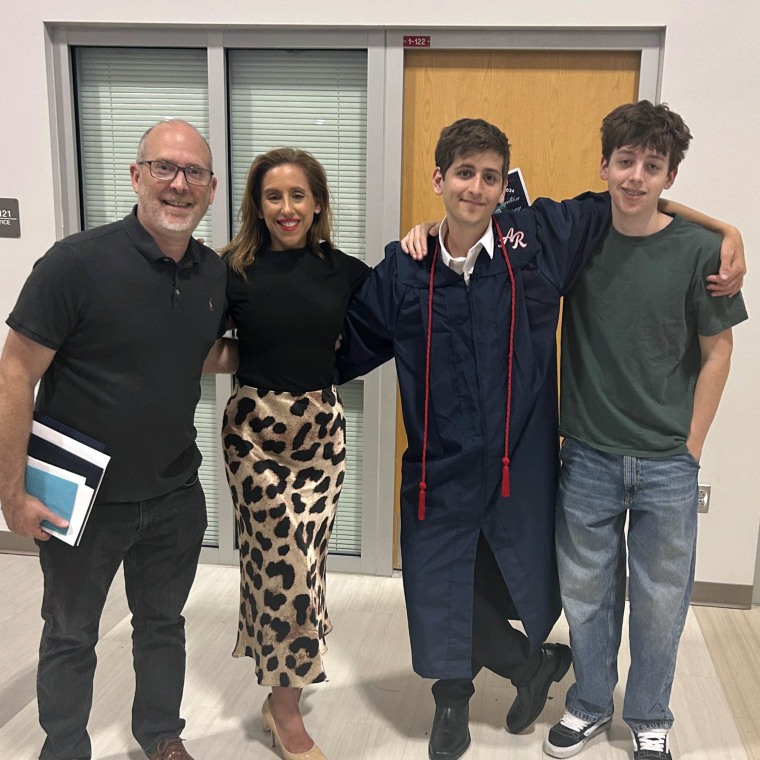

I was floating carelessly above Paris when suddenly I pictured my two small children, then ages 6 and 3, and my thoughts turned from my aerial adventures to the terrifying knowledge that they were at home, waiting for me. But my return home was without guarantee. The thought of my children brought me back in touch with my body and I started to try to talk myself down from the sky.

I cannot fly, I told myself. I need to stay grounded. I need to stay with my body, even if it’s in pain. I need to fight or I might not be able to come back.

Scared that I could become untethered like a helium balloon, levitating into the abyss, I started to resist an overwhelming desire to let go, terrified that it was too late and I had already passed the point of no return.

The power to save lives

“Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship,” Susan Sontag wrote in her book“Illness as Metaphor.” “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick.”

My passport to the kingdom of the sick was issued on that otherwise average December day via that seemingly innocent bump on my shoulder. My deliverance back to the kingdom of the well was provided by a prompt diagnosis and effective antibiotics.

My return ticket was not a direct path, however. In distinct contrast to the alarming alacrity with which sepsis had struck, the journey back to health would be full of difficult detours like debilitating vertigo, ocular migraines and nearly-immobilizing fatigue, and disconcerting delays as the recovery process dragged on many months, with some impacts lasting years. In the end, it wasn’t really a “journey back” after all; it was a journey toward a new self, not quite the same one I was before that fateful day.

But most of all, I was so fortunate that on that otherwise average day, I made it to the hospital in time.

When it comes to surviving sepsis, time is everything. For every hour treatment is delayed, the risk of death due to septic shock increases by 4%—9%, and as many as 80% of sepsis deaths could be prevented with rapid diagnosis and treatment, according to Sepsis Alliance.