Former Richmond city councillor Harold Steves has collected all sorts of stuff during his 87 years, including the contents of an old Chinese general store and an army canteen from the Second World War

In 1977 Harold Steves learned that the Richmond fire department was going to burn down Steveston’s historic Hong Wo general store “for practice.”

He had five days to salvage as much as he could.

He dashed down to the store, which had closed in 1971 and had been vandalized. But he still found all manner of stuff at Hong Wo’s, including what appeared to be an old opium den on the second floor.

“We took one of the walls apart, and we found a bag of white powder,” recounts the former Richmond politician. “We’re pretty sure that it was opium, about five pounds. The fish probably got pretty high — we threw it in the river real quick!”

Built in 1895, Hong Wo was almost as old as Steveston itself. As a descendant of the family that founded the community in 1886, Steves knew how historically important the store and its contents were.

“Basically it was a Chinese general store, when Steveston had a population equally Chinese, Japanese, First Nations and Caucasian, about 3,000 of each race,” said Steves. “It was a multiracial community, so they named the store Hong Wo, meaning ‘Living in harmony.’ ”

Some Hong Wo store fixtures went into an 1890s building Steves had moved to his farm. Cans, bottles and dry goods went into his attic and basement, where they sat for decades.

In 2022, Steves retired after five decades on Richmond city council. And he decided it was time to resurrect Hong Wo’s — in his basement.

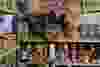

Hundreds of items from Hong Wo’s are now arranged on shelves.

There’s a big contraption that was used to clean rice, a funky display of Boeckh brushes, and a couple of boxes of price tags (19 cents, 30 cents) that look like they date to the 1930s.

There’s a glass bottle of Fraser River Fish Fertilizer, cans of Cap’n John Clam Nectar and bottles of Lucky Len Cluster Eggs. Naturally, there are also several brands of locally canned salmon, such as Smuggler’s, Lowe Inlet and Red Rose.

“They’re labelled Vancouver, but they’re from Steveston canneries,” he notes.

Whole house is like a museum

Steves lives on a farm that has been in his family since 1877. His house was built in 1917, and generations of the Steves family have been storing stuff in its attic. The collecting bug is in his genes — he sees value in most anything old.

This means there isn’t just one collection in the house, there are several. One end of his basement, for example, has been turned into an army canteen.

“There was an army camp on the farm in World War II, and right in front of the house, they had big guns,” he explains. “One of the (artillery) guns was so loud it used to shatter all the windows. They had to open the windows every time they fired the gun.”

A couple of the Hong Wo glass display cases have been set up in the canteen to display some of his army memorabilia, such as a tiny army uniform that he wore to inspect the troops as a child.

“I was a lieutenant-colonel in the army,” he said with a smile. “I was six, that was my summer suit. I’ve got a wool suit upstairs that’s stored away.”

The canteen holds all sorts of rare Second World War items, such as an old ARP (air raid prevention) helmet, an ARP booklet on how to “make your home your air raid shelter,” and a selection of old bullets from the guns on the army base.

He points out a small rocket that held a mini-parachute, which the army used for target practice.

“They shot a rocket in the air, and (the parachute) was attached to it,” he explains. “It would break open, the parachute would come sailing down, and they’d shoot at the parachute with those bullets.

“Some of them were called tracer bullets. They glow red as they went through the air, so you can see how close you were to hitting the target. The parachutes are coming down, and we’re running around the field, picking them up.”

He laughs: “I don’t remember for sure if the guns were firing over us or not. But they probably were.”

On the walls of the re-created canteen are some colourful Victory Bonds posters. One features an illustration of a farmer, his wife and their son filling a basket with corn, carrots, lettuce and tomatoes.

“Plant a Victory Garden,” the poster urges. “Our Food is Fighting. A Garden Will Make Your Rations Go Further.”

There is also a very cool poster showing officers’ ‘Badges of Rank’ in the Navy, Army and Air Force. The Navy had eight ranks of officer, for example, from sub-lieutenant to admiral of the fleet.

The poster was created by Player’s Navy Cut Cigarettes. Cigarettes were popular — there are two shelves of leftover tobacco tins from the canteen.

“The soldiers, all they did was smoke,” said Steves. “The only thing they sold to the soldiers was lunch, dinner and cigarettes.”

His whole house is like a museum. It’s home to about a hundred old gramophones, some self-contained in handsome wooden cabinets, others simple record players with stylish horns to amplify the music.

“Actually, my intent was to just have a gramophone collection, and set up the basement showing gramophones and nothing else,” said Steves. “Then all this stuff happened.”

In memory of Japanese Canadians who were interned

Upstairs, he has a bedroom dedicated to the Japanese Canadians who lived in Steveston before they were interned following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and Hong Kong during the Second World War.

“It’s largely from one family, the Kajiro family,” he said. “Mr. Kajiro was the principal of the Japanese language school. He was one of the first three people to be arrested.”

There are several letters from Kajiro to Harold’s father that were written during the war. They were sent in special “Prisoner of War Mail” envelopes, and stamped and initialled “Examined by Censor.”

The Kajiros lived across the street and were close to the Steves family — Harold played with their daughter Fumico. When the Kajiros were forced out of their home, Harold’s dad moved a lot of their furnishings to the Steveses’ house.

“The custodian of alien property wanted to sell their stuff,” he explained. “They sold (families’ belongings) and gave the Japanese nothing.”

The Kajiros asked Harold’s mother to sell their household items instead, and to send them the money. In appreciation, “at the end of the war, Mrs. Kajiro gave my mother her Japanese doll collection as a gift.”

Ten of the porcelain dolls are in the collection at the Steves family’s home. They represent the household of the emperor and empress, “a symbol of happiness and prosperity.”

“The girls in the family would get one doll each generation,” he said. “Assuming a generation is maybe 25 years, the emperor (doll) probably is from about 200 or 300 years ago.”

Helped draft B.C.’s Agricultural Land Reserve

Steves and his wife Kathy raised five kids in the house, which still has a small farm attached to it. But like many families, the Steves family suffered during the Great Depression, losing most of their dairy farm.

They built it back up in the 1940s and ’50s. But in 1958-59, much of their land was rezoned for residential. They couldn’t get a building permit to build a new dairy, so switched to raising beef cattle until 1967-68.

“Then they raised our taxes to the residential price, which was astronomical,” said Steves.

The family ended up selling most of their farm. Steves went on to win a seat for the NDP in the 1972 provincial election, and helped draft the Agricultural Land Reserve, which protects agricultural land from redevelopment.

Steves lost in the 1975 provincial election and went back to civic politics, and to collecting.

Go into any room in his house and he can spin a story on the contents, whether it’s the old bottles he dug out of Steveston’s first garbage dump or how he moved the 1890s building that holds the Hong Wo fixtures onto his property.

“(My friend) Scottie Robinson had a huge dump truck,” he recounts. “The reason the whole front end (of the building) is out is (because of) how we moved it. We took the front out and he backed the truck in, shored it up and we drove it home with a truck inside the building.”

He laughs at the memory: “We parked it, and put a foundation under it.”

He had hoped to move the 1890s building to a park, but it never happened. But he is determined to see the contents of the Hong Wo store moved to the Phoenix Net Loft at the Britannia shipyard historic site, which has been deconstructed but will be rebuilt.

In the interim, it’s safe in his basement.